India has always been a profoundly violent country. Yet the vocabulary about this violence remains deeply muted and limited. The routinized violence experienced by the country’s marginalized—Dalits, Muslims, Adivasis, poor, and women—is not only denied but also hidden behind a language of neutrality. Like in Adrienne Rich’s words, “This is the oppressor’s language yet I need it to talk to you,” the language used to report, narrate, and understand these acts of violence and dehumanization remains the language of the oppressor.

The contemporary moment in India—lynching, caste violence, and judicial apathy that repeatedly fails to convict murderous men—thus demands that we think about these grotesque acts of violence not as a spectacle but as a continuum, not in isolation but in relation to language, history and media representations of caste and religion. In 1996, African-American reporter and then South Asia bureau chief of Washington Post Kenneth J. Cooper wrote, “India’s majority lower castes are minor voices in newspapers.” After 20 years, Cooper observations remain valid. Here oppression, erasure, and obfuscation of truth all occur in copy-editing.

In India, there are only a handful of reporters who have now consistently and accurately reported on the recent upswing in violence. In this conversation, Suchitra Vijayan of The Polis Project speaks to Sagar, a Delhi-based journalist who uses only one name. From the frontlines of reporting on caste and identity-based violence comes a tour de force of observations that implicates the nature of media, the politics of identity and representation, and most importantly how truth dies in the pursuit of justice. Sagar’s candid and raw considerations shine a stark and disturbing siege against India’s more vulnerable and how the fissures of caste and religion have grown into epistemic fractures that have birthed a new republic—of fear.

By

Polis: You have done some of the most comprehensive reporting on lynchings and caste violence for The Caravan. Can you tell us about how and why you started reporting on these events? Sagar: I started as a crime reporter in a regional English daily in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, where I also covered the State Human Rights Commission. There were many cases of caste violence in the city and districts away from the capital, and I would meet people coming with their complaints and petitions. It was a discovery even for me. These cases, even when involving serious crime, many even in the city, were never reported. These included crimes like someone’s house being demolished because they belonged to the Scheduled Caste, or physical assault. Caste was the central point of any crime. Birth and identity were the basis on which people were attacked. Not just individuals, entire communities were attacked with…

Related Posts

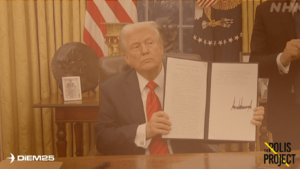

Donald Trump’s Master Economic Plan I Opinion by Yanis Varoufakis