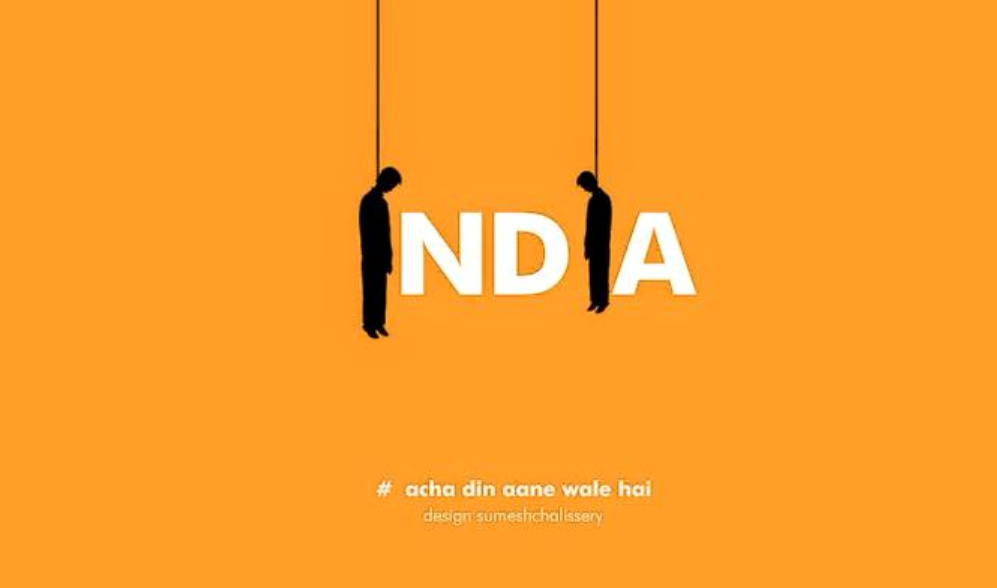

A lynching is a public, extrajudicial execution. Once we begin with this definition of lynching, the claim made in a recent Print.in article about a spate of WhatsApp rumor based lynchings that “There is, sadly, no political angle in these killings. There’s no Hindu-Muslim dispute, not even caste. There’s no India-Pakistan, no BJP-Congress, no jihad or Naxalism, no RSS or Kashmir, no statements and counter-statements by politicians”, stands in correction. Indian journalism and its reporting around lynchings have, oddly, focused on the medium as the messenger – WhatsApp – rather than the nature of violence, and its long history of targeting the ‘other’.

Acts of collective public violence do not occur in isolation. These seemingly independent events are linked to broader social, economic, and political forces. Framing these acts as “disciplinary violence” against an “errant” individual out of “righteous anger” or “anxiety” does great harm and disservice to understanding and preventing what is now an everyday enactment of grotesque violence.

For the past year, our team of researchers at The Polis Project’s Violence and Justice Lab has been building a data set on collective public violence and justice in India since 2000. Our dataset logs acts of mob-based violence – lynchings, massacres, riots, gang rapes, etc. involving two or more persons – and traces how these acts are processed through the justice system. We have found collective public violence to be steadily on the increase since 2000. This could be a function of better and faster reporting or a function of the availability of such information in non-traditional news spaces. However, what we are rapidly seeing through our data is that one cannot make either of the claims – that Indian society was ever tolerant, or, that violence has not been on the upswing.

India has always been a profoundly violent nation with a legal system that is skewed in favor of the country’s ruling elite. This is why perpetrators of such violence are often vindicated, while the most marginalized people and their bodies are the victims and sites of such violence. Recent repetitions of collective public violence against several types of victims, its recording and dissemination demonstrate that Indians have no fear of or faith in the institutions of the state to dispense justice.

“Lynchings were most common in regions with highly transient populations, scattered farms, few towns, and weak law enforcement – settings that fuelled insecurity and suspicion.” The term “lynching” has often been traced back to William Lynch’s ‘Lynch Laws’ in an America driven by slavery as early as 1780. In 1782, Charles Lynch, a justice of the peace, is believed to have used the term to authorize extra-legal punishment of Loyalists. However, these assertions are the subject of much debate. A lynching is a product of a time with weak state penetration, where men and women frequently took the law into their own hands to punish those they thought had committed some wrongdoing. Often such lynchings in the American South between the 1880’s and 1920’s was carefully organized. Posters would be put up in advance, leaders of society and local notables like the clergy often attended these events. Photographs of the…

Related Posts

Donald Trump’s Master Economic Plan I Opinion by Yanis Varoufakis